Burnt Island Light

Maine boasts 65 lighthouses along its craggy coastline and on offshore i slands—the second highest number per state, behind Michigan. Each Maine lighthouse has its own distinctive characteristics: Nubble Light in Cape Neddick glows red; Goose Rocks Light off North Haven has its keeper’s quarters (in which up to six adventurous souls can stay overnight) inside the 51-foot-tall tower, and West Quoddy Head Light in Lubec sports red and white stripes. Burnt Island Light in Boothbay Harbor has at least two distinctions: it was the first lighthouse built after Maine became a state and the oldest original lighthouse (Portland Head Light is older but was built when Maine was still a Massachusetts colony and has been altered), and it is the only one to offer visitors a living history experience.

From the summer of 2003 until a restoration project put the program on hiatus this year, twice a week a team of volunteer actors played the roles of keeper Joseph Muise, his wife Anna, and their four children, reenacting life on the island as it would have been in 1950. “I chose to restore it to 1950 because I have the best record of that time,” says Elaine Jones, education director for the Maine Department of Marine Resources. Having studied biology in college, Jones says that history didn’t interest her “one iota” before getting involved with Burnt Island Light. She is responsible for spearheading the acquisition of the island, restoring the buildings, and developing its extensive educational programming. “The reason I went after Burnt Island wasn’t for historic preservation but for a place to teach schoolteachers about marine science,” Jones says. “Here was a five-acre island with every imaginable habitat related to the marine environment.”

Jones first saw the island in 1996, after Congress passed the Maine Lights Program, legislation that provided for the transfer of 27 Maine lighthouses from the Coast Guard to other government organizations, local towns, and nonprofits, with covenants stating that the properties had to be maintained for preservation, education, conservation, and recreational purposes. Conceived by Maine photographer Peter Ralston as a way to save lighthouses that were in danger of being demolished by the Coast Guard, the program was funded by the sale of 300 signed prints donated by celebrated painter Jamie Wyeth.

Through the Maine Lights Program, in 1998 Burnt Island Light was deeded to the Maine Department of Marine Resources. Jones had plans to create an education center on the island and restore the existing buildings, but because the lighthouse was on the National Register of Historic Places, she couldn’t make any changes unless they were historically accurate. “Then I was off to find the pieces of my puzzle—and that’s when I got hooked on history,” recalls Jones. Her research took her to the National Archives and the Coast Guard Historian’s Office in Washington, D.C., as well as the Coast Guard Civil Engineering Unit in Providence, Rhode Island. She read the log books that keepers maintained from 1868 to 1936, notably those of James McCobb, who worked on Burnt Island from 1868 to 1880 and kept a highly detailed record of his days, including a description of his wife’s death. “He was the most colorful person,” says Jones. “I know so many fascinating things about his family and his life here.” Most significant for her research and for the education mission of the island, she was able to track down 14 former keepers or their family members who were still alive; their stories inspired the creation of the living history program. “I interviewed four of the Muise children in 1999,” says Jones. “Two of them—Adele and Ann—are still alive in their eighties.” The Muise family donated back a number of household items, including Joseph Muise’s shaving mug, a high chair, and a commode.

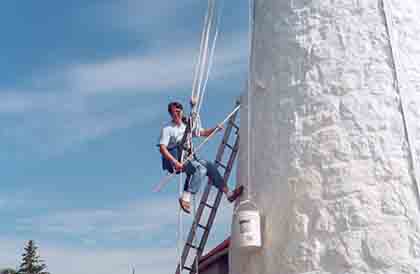

When the lamp in the Burnt Island Light tower was first lit—with ten Lewis parabolic reflector lamps burning whale oil—on November 9, 1821, keeper Joshua B. Cushing and his family lived next door in a house made of granite quarried on the island. By the 1850s, whale oil was deemed too expensive, so the Lewis lamps were replaced with a Fresnel lens, powered by kerosene. Whale oil is not highly combustible, so it could be stored in the lighthouse—curved niches in the interior brick walls show where the barrels were kept—but a new brick oil house had to be built to store the kerosene. At the same time, the original stone dwelling was torn down and replaced with the wooden house and covered walkway linking it to the lighthouse that still exist today. To mark Burnt Island Light’s bicentennial in 2021, the house and the tower are under restoration. Masonry contractor and lighthouse specialist J.B. Leslie Company of South Berwick is repairing the stonework in the tower and the foundation of the house, and Marden Builders of Boothbay Harbor is restoring the exterior of the house, installing 27 historically correct windows (circa 1950) provided at cost by Marvin Windows and Hammond Lumber Company.

The restoration project was financed through a $350,000 “Keep the Light Burning” campaign by the Keepers of Burnt Island Light (KBIL), a nonprofit formed in 2008 to assist Jones and her assistant, Jean McKay—co-creator of the living history program—with the maintenance of structures and the development of programming on the island. Previous fundraising efforts financed a 32-bed education center where Jones hosts professional development workshops for teachers and overnight trips for schoolchildren. KBIL volunteers maintain the recreational aspects of the island—trails, picnic tables, boat moorings, and the dock—and run the living history program, training volunteers to play members of the Muise family. “Once the children get out here they are so excited,” says Howard Wright, a founding member of KBIL and a keeper for 13 years. At 91, he’s retired from the role, but says, “If there was an emergency I think I could still spin a yarn. One visitor told me, ‘This has Williamsburg beat by miles.’”

With Jones retiring in December, the future of the living history program is uncertain. She has pledged to return next summer and says she is “not leaving here until these buildings are in top-notch condition” for their bicentennial and beyond. “I do hope it’s a legacy for me and that my name is attached to this period of time when we rescued the lighthouse,” Jones says. “The experiential learning that takes place here on the island is second to none. My dream now is for this community to embrace this island—their lighthouse, their history, and their ancestors who served here.”