Inside Out | The Prints of Mary Cassatt

A new exhibition at the Colby Museum of Art showcases the experimental printmaking of an artist mostly known for her paintings

Imagine life in Belle Époque Paris, the center of the modern art world in France. You are a 33-year-old American woman, an artist. After studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, you find your work has been well received, and you are what people would call “successful.” But something is missing; there is a creative craving you haven’t yet satisfied. This was Mary Cassatt’s situation when, in 1877, Edgar Degas introduced the burgeoning artist to printmaking. The medium, a very physical and somewhat dangerous one (in the nineteenth century especially) involving ink, sharp metal, resin, and acids, provided Cassatt with the freedom to explore her own artistic agenda. She quickly became the equal of any printmaker of the period. It was in exhibiting with the Impressionists that, according to Justin McCann, the Lunder Curator of American Art and Whistler Studies at Colby College, Cassatt is noted to have said, “At last I have absolute independence.”

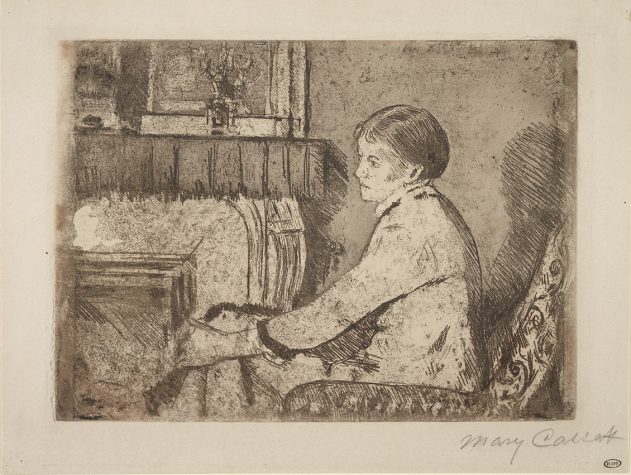

Inside Out: The Prints of Mary Cassatt, a new exhibition at Colby College Museum of Art featuring works primarily donated by Peter and Paula Lunder, explores a different side of an artist who is known primarily for her later-in-life “mother and child” paintings. The prints Cassatt produced during this earlier period reveal her boundlessly creative process and experimentation. What makes the works on display so unique is that many of them are trial proofs—prints that Cassatt would have pulled only one time to check the development of the composition.

There are three versions, for example, of In the Opera Box. From the first to the third print, you can see Cassatt lightening shadows and abandoning certain configurations. “The nature of the collection allows us to see inside her head and the way she is working and changing,” says McCann, who co-curated the show with the chief curator at the Portland Museum of Art, Shalini Le Gall. “The collection demonstrates an artist who is willing to innovate, to explore, to make mistakes, and to even abandon works.”

Due to the gender norms of the period, Cassatt focused mainly on modern, upper-class women—either their social rituals, like driving through the park in Woman Driving in a Victoria or getting ready to go out in At the Dressing Table, or scenes of domesticity, like the standout color print in the show, Young Thomas and His Mother, which inspired the color motif for the exhibition and catalog designed by Rita Jules of Miko McGinty. As McCann says, these scenes could reinforce stereotypes that still adhere to femininity and a woman’s place in the world, but Cassatt eschews sentimentality: “She’s not a voyeur, she’s not exploiting them in any way. It seems so natural and so casual, and I think it’s something that draws us in as viewers.”

The show was scheduled to open in 2020, and of course it did not. But perhaps this timing, one where visitors to the museum emerge from a locked-down interior life into a newly opened world, will resonate. “Scenes like Waiting scream anxiety,” says McCann. “She is just staring out a window. And I did that several times, you know? I think because of the pandemic people can relate to that.” Inside Out: The Prints of Mary Cassatt will remain on view until November 1.