Anatomy of an Artist

PROFILE-April 2010

by Carl Little

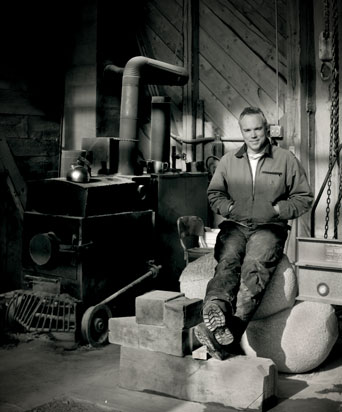

Photography Sean Alonzo Harris

From Steuben, Maine, to Japan and Egypt, this sculptor has learned the ways of stone

On a frigid morning this past December, the sculptor Jesse Salisbury welcomed a visitor to his humble abode off Joe Leighton Road in the woods of Steuben, a small coastal town in Washington County. Seated in the warm kitchen of the house he grew up in, the 37-year-old Salisbury was coming down off a kind of artistic high. The day before, in equally brutal cold, he had successfully installed his Anatomy of a Boulder sculpture at the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland. With a little less than nine hours of daylight to work with, he and his assistants had moved fifty pieces of heavy granite over a hedge and into the museum’s sculpture garden. The artist enjoys working on a large scale, and he loves the stones native to his region: granite and basalt. Indeed, the stone he used for Anatomy of a Boulder came from a nearby gravel pit. The 20-ton granite behemoth was split into four pieces and transported to Salisbury’s studio. There, after further splitting, he carved it into the dynamic abstract sculpture now on view at the Farnsworth.

The title of the piece underscores Salisbury’s approach. Whatever the size of the sculpture he is working on, whether it’s abstract or figurative, the rock must be intensively studied beforehand to understand its physical makeup. Transforming stone into art takes a great deal of calculation; it’s “mathematical and proportional,” says the sculptor, as much as it is aesthetic.

Salisbury began carving as a student at Ella Lewis Elementary in Steuben, from which he crossed the road to work in Peter Weil’s sculpture studio after school. As a teenager, his family moved to Portland, where his father ran the fish auction, and then to Japan, where his father served as a fisheries attaché. He completed high school in Japan, then stayed on to apprentice with a Japanese potter.

His artistic studies became more focused at Colby College. An East Asian studies major with a dual minor in Chinese and art, Salisbury took sculpture every semester. Harriett Matthews, a master sculptor on the Colby faculty, pushed him in new directions, but he always remained committed to stone. He went on to study at the Art Students League in New York City, learning to carve marble and limestone in the European tradition. To support his burgeoning career in sculpture, he spent summers fishing in Alaska.

Salisbury’s introduction to “big time” sculpture came on a return trip to Japan in 1997, where he had been offered the position of assistant to the sculptor Katsumi Ida. Ida proved to be a great inspiration: not only did he work in granite and basalt, he had also started an international sculpture symposium in his home town.

Salisbury attended that symposium the following year and was delighted to encounter Atsuo Okamoto, a sculptor he had discovered as a student at Colby in Janet Koplos’s seminal book Contemporary Japanese Sculpture. Okamoto was a master at splitting stone, a skill that was quickly becoming Salisbury’s passion.

After returning home to Maine, Salisbury began assembling the tools he needed to tackle stone on a more ambitious scale. He bought an air compressor, and then a crane; a power hammer and wire saw came later. He began collecting stone from local quarries and gravel pits. He also had several exhibitions at Tunk River Sculpture and Gardens in Steuben, which was owned by his first teacher, Peter Weil, and Weil’s wife, Jane. Proceeds from the shows, in addition to what he earned working as a landscaper, moved him closer to his dream of creating more monumental sculpture.

As his style a

nd skills evolved, Salisbury became comfortable working in both figurative and abstract modes, and he frequently worked in both. Over time, the artist kept returning to the stone-splitting techniques he learned in Japan. He loved exploring the character of each stone and developing new ways to reveal subtle textures and dynamics.

In 2004, Salisbury returned to Japan to take part in the Nasunogahara International Sculpture Symposium Exhibition in Otawara City, Tochigi. Among his fellow participants was sculptor Kazumi Hoshino. The two artists fell in love and later married. Today, they have a 3-year-old son named Ren. Salisbury’s experiences in Japan led him to organize his first international sculpture symposium, which was held at the Round Top Center for the Arts in Damariscotta in 2004. He went on to found the Schoodic International Sculpture Symposium in 2007, where artists from around the world, and from across Maine, are invited to create sculptures using local stone.

The second Schoodic Sculpture Symposium happened last summer. Even larger pieces were produced and on display, thanks to better equipment and more technical support provided to visiting artists. When the finished pieces are sited, a total of thirteen Downeast communities will be the lucky recipients of world-class public sculpture. A third symposium is planned for 2011.

Salisbury has shown his work in venues across Maine, from the University of New England Art Gallery to the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens. He also participated in the 2008 Aswan International Sculpture Symposium in Egypt. As he told Letitia Baldwin, arts editor at the Ellsworth American, “There you are carving right next to things that are thousands of years old.”

Today, Salisbury is able to make a living from his work. Private commissions, gallery sales, and a variety of special projects keep his days filled, including a Percent for Art piece he recently completed for a new school in nearby Gouldsboro. “It’s amazing,” the sculptor says, reflecting on the last decade of his career. “The international connections, the Maine connections, developing the symposium—they seem totally separate, but they come together, create momentum.” It will be exciting to see where that momentum carries this consummate stone splitter next.

Salisbury is featured in “Four in Maine: Site Specific,” opening at the Farnsworth Art Museum on April 17. Fellow artists are Kazumi Hoshino, Aaron Stephan, and Warren Seelig. Salisbury is represented by June Lacombe Sculpture in Pownal and the Courthouse Gallery in Ellsworth. The 2007 Schoodic Sculpture Symposium is the subject of the film Rock Solid by Richard Kane. Jesse Salisbury: jessesalisbury.com