Adaptive Reuse

Architect Mike Sealander on converting dilapidated building into spaces that will stand the test of time

One doesn’t have to wander far from the MH+D offices to find excellent examples of historical buildings that have been given new life. Nearby, the former offices of the Portland Press Herald have been transformed into a chic 110-room boutique hotel and restaurant that contributes to the vibe and vitality of Portland’s downtown. On Merrill’s Wharf on Commercial Street, the partners of Pierce Atwood invested in converting one of the largest and oldest buildings on Portland’s waterfront into a beautifully appointed law firm. And across town, the 1888 Baxter Building has been reimagined as a thoroughly modern and creative office space for the VIA Agency. MH+D asked Mike Sealander to tell us more about making old buildings new again.

Q. How did you become interested in adaptive reuse?

A. My wife and business partner, Robyn, and I studied architecture at Columbia University in a program that I would describe as “intensely urban.” Our studio training challenged us to design solutions within an existing inner-city fabric—designing or adapting a building in the context of the buildings that surround it. For one of my studio projects, I was assigned a hypothetical reimagining of the High Line, a historic freight rail line elevated above the streets of Manhattan’s West Side, which, years later, was in reality repurposed into a tremendously popular linear public park. This type of project, envisioning a part of the built environment in a very new way, was typical of design studios at Columbia, and the thought processes I learned there have stayed with me.

Q. What are some of the best applications?

A. People tend to look favorably on older buildings because they have design details and character that newer buildings sometimes lack. The buildings that have survived a century or more are the best of their era—the lesser buildings from the past are gone. Timely interventions kept these buildings current by adapting the design as the world around them changed. Adaptive reuse is not so much a matter of preserving the old as it is reenergizing something old by adding new systems and new uses. There are some wonderful adaptive reuse projects in Maine, such as Platz Associates’ revitalization of the Bates Mill, a former textile factory founded in 1850 in Lewiston. This project, an old industrial building that suffered from years of neglect, had a multitude of challenges, such as underground streams, deteriorating structural elements, and grossly inadequate safety features. The new space houses freshly designed clean and sound apartments, commercial office spaces, and a small museum.

Q. Can you give an example of adaptive reuse in one of your projects?

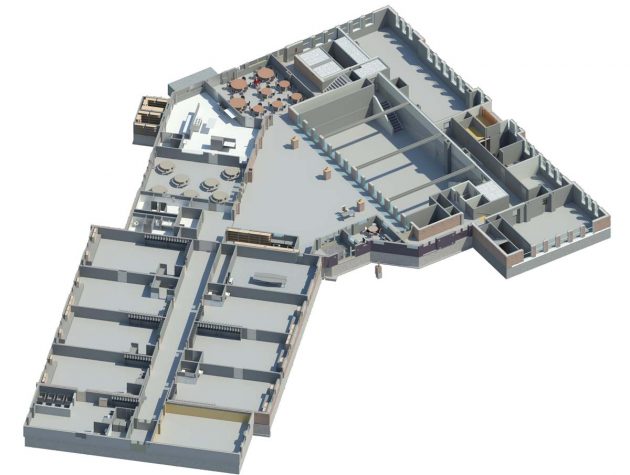

A. We worked on the Bryant E. Moore Community Center project in Ellsworth, adapting an abandoned school into a center for community events, senior services, and childcare. The building was uninsulated, and the flow of the design was impeded: on the main floor one had to go through the gym to get from one side of the building to the other. Of course, no old building was built to provide accessibility to people with disabilities, and a series of half-hearted renovations had compromised many redeeming original features, such as a gorgeous theater and really great windows. So we ripped out and replaced stairs, put in an elevator, straightened out circulation, and upgraded the exterior envelope with spray foam and energy-efficient windows. People speak favorably of the work we did integrating the old and new, but the majority of the effort we made occurred above ceilings and inside walls, including asbestos abatement and all new electrical, plumbing, and mechanical systems.

The three principal players were the City of Ellsworth, the Down East Family Y, and Friends in Action, which provides services to seniors. The idea was to create a place where the young and the old would share the same building, intermingle, and benefit from each other’s presence. We had a lot of interesting conversations about how much and what type of interaction was best. In the end, seniors do have their side, and the childcare activities have their side, but the overlap is available, and it works.