Lakeside Magic

FEATURE-May 2011

by Bruce Irving | Photography Trent Bell | Styling Meagan Gilpatrick

The Maine cottage comes of age

Future archeologists may come to describe the evolution of the Maine cottage as a three-step process.

In the beginning, they were humble, hand-built structures that provided basic shelter from the elements, a place to cook, and an outhouse, preferably away from the lake. What they lacked in, say, electricity, they made up for in beautiful materials (often sourced on-site) and the hard-to-define grace that our forebears brought to the shapes and proportions of everything they built—the pitch of a roof, the size of a dormer, the rough perfection of a stone chimney.

Next came the post–World War II “box” years, when a kind of get-’er-done ethos informed the function-over-form thinking of modernism, and tight budgets, practicality, and the American dream

populated multi-lot developments with simple ranches. Clean, simple facsimiles of suburban architecture seemed like a perfectly good way to bring domesticity to the water’s edge.

But now the humble cottage has entered a new age, and genuine architectural prowess is being brought to bear on that seemingly simple homeowner request: “Just give me a nice place I can escape to.” Compared to the old days, the challenges are many, whether it’s the nuts-and-bolts of zoning issues and energy codes or the quest to update the character and beauty of the old camps for modern living.

Portland architect Will Winkelman, of Winkelman Architecture, has a strong command of the practical and more elusive aspects of building near Maine waters. He has lived on Peaks Island in Casco Bay for twenty-five years, designing dozens of camps, cottages, and homes there and throughout the state over his quarter century in the business. When the San Francisco–based owner of a lot on Raymond’s Panther Pond asked him to imagine a new family getaway, he knew where he would have to start: zoning.

“The constraints were tremendous,” the homeowner recalls. “But Will and his office presented us with three excellent versions of the house, each based on what kind of permissions we might get.” In the end, Winkelman and builder Bill Symonds of Casco’s Symonds Builders were allowed to demolish a pre-existing 1960s home and replace it with a pair of buildings that form a simple compound. “Those two buildings started from the inside,” says Winkelman. “The plan has to work first, then you decide what the structure will look like.”

For the owner, who had spent boyhood summers on the pond “waterskiing behind a six-horsepower dinghy,” the classic cottage look was important. He didn’t want to reproduce the boxy structure he purchased, but he also didn’t want something showy. One of the first steps in the process was bringing Winkelman to see the rustic, unwinterized camp his parents own nearby. “It was important to him and his wife,” says Winkelman, “that this house not be some kind of palace. They said to make it ‘strong and unique,’ and I think that’s what we gave them.”

From the start, Winkelman had a few foundational features in mind. One was privacy. He sited the rear building—a 900-square-foot “bungalow” that holds a guest suite, garage, and home office—so that it functions as a screen. “You leave your cars on the other side of it,” he says, “then pass through the portico and into ‘camp mode.’” In front sits the 2,600-square-foot main house, which is surrounded by pines and faces the glorious pond. It’s a delightful collection of smaller living spaces tied together with cedar shingles, dark green windows, and a copper raised-seam roof. Those carefully selected materials provide another core feature—extremely low maintenance requirements. Aside from the long-lasting, factory-applied window paint, the exterior of the home has no man-made coatings; the wood and copper will continue to patina, the house settling into its site with each passing year. The only gutters are short runs over doorways; everywhere else, rain and snow freely fall off the roof and into a pebble drip strip. “When I first started out,” Winkelman says with a laugh, “I thought architecture was about making cool, good-looking buildings. What I know now is that it’s all about holding back the elements.”

Winkelman also faced another challenge. Most houses with a waterfront view are long and thin to maximize the view and bring natural light into every room. Lot-line setbacks and volume restrictions, however, prohibited this kind of design. The solution? Create a central courtyard that acts as a light source, a focal point, and a space from which all the beauty of the setting can be taken in. Best of all, the room that does all of this magic is as traditional as can be—a screened porch.

But where our forebears might have been content with wide screens, some exposed rafters, and a few rocking chairs, the porch on Panther Pond is a tour de force. An asymmetric layout, sophisticated timber trusses, a south-facing glass roof, the beautiful native stone of the house’s chimney, and peeled white-cedar posts with invisibly inset screen panels combine to make the porch a magnetic gathering spot. “A gin and tonic out there is just about the best gin and tonic ever,” says the owner.

Putting it all together required exceptional skill and craftsmanship. Symonds rigged special jigs along the round, irregular cedar posts that allowed him to cut out precise channels for the screens. The entire porch sits above an air-conditioned basement space, which necessitated a

leakproof underlayment. To prevent the cedar posts from wicking water, Symonds devised a flashing-and-bayonet system that invisibly holds the posts above the underlayment, yet still allows them to support the massive roof above. “It was all part of the fun,” Symonds says, “though come February we got a little tired of that cold west wind whipping across the ice.” He and his crew started work in October 2008, and their clients arrived in mid-July to find a finished house—an amazing feat. “Bill pledged to me that we’d be his only job,” says the homeowner, “and he delivered, pedal to the metal, wire to wire.”

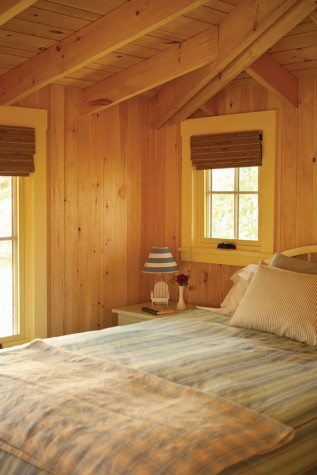

Inside, the house is a symphony of wood: antique resawn oak for the floor, recycled barn-board walls, white-pine roof timbers, random-width pine ceiling planks, and—anchoring it all—a peeled white-pine post taken from Symonds’s own woodlot. The dark red kitchen cabinets are topped with honed Monson slate, and light streams in from a dramatic custom skylight installed above the spreading timberframe. All the details are spot-on—from the accordion doors that open between the dining room and the screened porch to the studied casualness of the spacing between wall and ceiling boards to the spectacular stonework by local mason Phil Shane. Everything was purposefully selected and ideally situated, and that’s no accident. “I cut my fees in half for the last 10 percent of a project, which is when things can go wrong,” says Winkelman. “That way the client and builder will keep calling me right to the end.”

And the policy worked. The wife, a busy mother of three, points to the fireside swivel rocker in the living room. “I sit there and marvel at how all the beams come together overhead,” she says. “Then I turn to see the lake…and I’m just awed by what we have here.” Lucky for their friends and family, they don’t keep it all to themselves—last summer they logged seventy-eight guest nights.

Clearly, the evolution of the Maine cottage is more than a science. “I like our place in San Francisco,” says the husband, “but this house is magic.”