The Life Aquatic

South Freeport is Cumberland County’s Secret Seaside Hamlet

Most visitors see only a fraction of Freeport. Each year, over 10 million people make the requisite pilgrimage to L.L.Bean on Route 1— renamed Main Street where it cuts through town—and hit the neighboring outlets, boutiques, and restaurants housed in quaint nineteenth-century structures. But those who know only the commercial side of Freeport are missing out. Beyond the shiny stores, winding country roads lead inland to the wooded hills of Pownal and out to the peninsulas of Wolfe’s Neck and Flying Point, past grazing cows to quiet coves and the grassy banks of the Harraseeket River, which empties into the heart of Casco Bay. Freeport is on the ocean, and yet many come and go without ever catching a glimpse of blue.

About three miles from the L.L.Bean campus, the waterfront village of South Freeport is part of Freeport proper but has its own post office, zip code, and quiet Main Street flanked by old homes and large trees through which the sun casts dreamy, dappled light. The road leads down a hill to the town dock, tucked between Brewer South Freeport Marine and Strouts Point Wharf Company—two full-service marinas and boatyards—and adjacent to Harraseeket Lunch and Lobster Company, a casual seafood joint where savvy tourists wait in line at the take-out window with bottles of cold chardonnay (it’s BYOB). On the other side of Strouts Point is the Harraseeket Yacht Club, a 250-member organization and the community’s cultural anchor.

Elizabeth Martin, the 19-year-old captain of the Lilly B. ferry to Bustins Island, which leaves from the town dock three to five times a day, says that for the first half of her life she hardly left South Freeport, “which is funny,” she adds, “because a lot of people don’t even know it’s here. It’s nice because it’s part of Freeport but you don’t get all of the out-of-towners who go to the big shops. It’s more of a little neighborhood.” She attended Merriconeag Coast Waldorf School (now known as Maine Coast Waldorf School) then located just around the corner from her house. Today, that school building on South Freeport Road is home to the small, private elementary school L’Ecole Française du Maine—the only French immersion school north of Boston. Growing up, when school let out for the summer, Martin spent her days sailing at the yacht club, which boasts a robust youth program open to members and nonmembers alike.

For Painter Soule, a recent Freeport High School graduate and a crew member on the Lilly B., it was much the same: “When other kids were getting their first 10-speed bike, I was getting my first 10-horsepower boat. I grew up on the water.” This was also true for generations of Soules before him. In the nineteenth century, his ancestors built boats in South Freeport and the nearby village of Porter Landing. The Harraseeket River—historically free of ice and noted for its sheltered port—gave Freeport its name when it split from North Yarmouth in 1789, indicating how essential its waters were at that time.

While no longer the commercial center of Freeport, South Freeport remains a working harbor. On a Saturday afternoon in the summertime the scene at the town dock is one of organized chaos. Clammers come in with the tide, hauling bags of bivalves out of beat-up skiffs; sailors in boat shoes and wind breakers are trailed by seafaring pups; and families headed to the seasonal community of Bustins Island disembark from cars packed to the gills with coolers and L.L.Bean totes. From a tiny stilt structure, the harbormaster oversees the scene, which includes hundreds of fishing boats, wooden sailboats, and motorboats, most of which belong to locals. (The dock reserves 90 percent of its moorings for Freeport folks.) After Labor Day, when the islanders begin to shutter their cottages and the pleasure crafts are removed from the water, the fishermen keep at it. Heidi Gerquest, a designer and co-owner of the local textile company Fragment Studios, lives on Main Street and can hear them driving down to the town dock at the crack of dawn each morning.

A native of Brooklyn, Gerquest had lived in Portland for several years before she and her then husband discovered the villages of Porter Landing and South Freeport in 1993. “We were driving around and stumbled upon the area and thought, ‘This is where we want to live,’’’ she says. “The place seemed kind of magical, and I loved all the old houses.” Gerquest discovered a strong sense of community in Freeport, liked the convenience of living only 20 minutes from Portland, and, as an artist, found herself in good company.

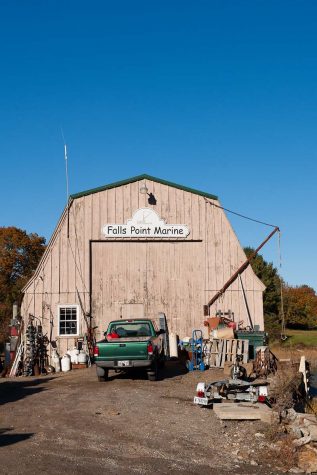

“When I first moved to the neighborhood, someone invited me to join a life drawing group,” she says. “And it seems like more and more artists have moved here since.” Her daughter is now in college in New York, and the streets around her are filling up with a new crop of young families. “South Freeport is a wonderful place to raise children,” she says, commending the school system and “low-key” Harraseeket Yacht Club, where her daughter learned to sail. During the club’s annual Youth Regatta, her neighbor Carter Becker, owner of nearby Falls Point Marine, parks his barge in the river and passes out hamburgers and hot dogs to the sailors.

Gerquest also loves South Freeport’s proximity to varied landscapes and protected land. “When we didn’t have money to take a vacation, we used to get a campsite at Wolfe’s Neck Farm [in Freeport] for a week or two,” she says. “If we forgot something we’d run home or to Bow Street Market.” Just west of the campground is the seaside Wolfe’s Neck Woods State Park, and to the east is Flying Point peninsula, which dips into Maquoit Bay—miles of scenic beauty, in other words, located just over the river (and through the woods) from bustling Route 1.