Beasts of Print

THE CANVAS-October 2011

By Britta Konau

Dahlov Ipcar, Holly Berry, Holly Meade

Dahlov Ipcar, Holly Berry, and Holly Meade are printmakers who focus primarily, or exclusively, on animals, which they depict in varying degrees of stylization. Ipcar’s lithograph was drawn with a grease-based medium on a zinc plate that was then washed and etched before inking and printing. Berry has contributed a multicolored linocut for which she carved several pieces of linoleum, one for each color or texture and another for the line design. And Meade is represented by a woodcut design she carved into a single block of wood. These different printing techniques allow for a range of image qualities that vary in value, texture, and boldness of line. Coincidentally, all three artists are also avid illustrators of children’s books.

Dahlov Ipcar

Dahlov Ipcar was born in 1917 to eminent modernists William and Marguerite Zorach. Growing up in an extremely creative environment, Ipcar never took formal art lessons, but her artistic talent was always encouraged. She is a painter and printmaker who has also illustrated and written more than thirty children’s books, many of them recently reissued. She has painted murals for 11 public buildings and has received numerous awards, including honorary degrees from the University of Maine, Colby College, and Bates College. At age 21, she had her first solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, and her work is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, and Brooklyn Museum of Art, among others. Ipcar is represented by Frost Gully Gallery in Freeport.

Dahlov Ipcar’s signature style developed around 1960 when she applied the characteristics of fabric patterns to her paintings. Her compositions feature fluid lines, clearly delineated shapes, vibrant colors, and complex divisions of flat pictorial space. The Fauvism and Cubism she encountered in her childhood influenced her stylistically, but thematically she has followed her own vision from the beginning—since she was a child, animals have been her favorite subject matter.

Ipcar feels an affinity to animals, and her life has always included several of them. She is particularly intrigued by the shapes, designs, and colors that distinguish species and closely observes them in real life. However, she neither sketches nor photographs the animals she encounters—instead she works from memory and leaves realism behind. Balancing abstract and representational tendencies, her work displays underlying spatial and coloristic rhythms of energy that are amplified by the depicted animals, which are almost always in motion, prancing, jumping, or grazing. Ipcar’s flora, however, is not based on observation at all: “I make up my botany,” she admits.

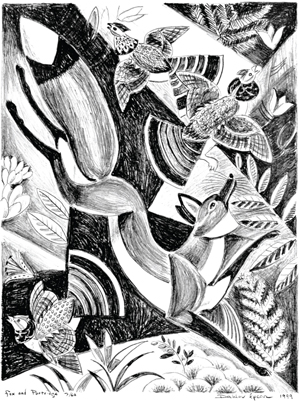

The diagonal placement of the fox in Fox and Partridge dramatizes its predatory movement. As he pounces into a gathering of partridges, the birds anxiously scatter. Animalistic instincts remain intact, yet Ipcar never depicts the harsh outcomes. Instead, her images are fanciful and decorative without losing their basis in reality. At age 94, Ipcar does not think she’ll be running out of ideas any time soon. “Ideas for pictures keep coming to me,” she says. “My mind is just full of wonderful things.”

Holly Berry

Holly Berry was born in Maine and now lives on a farm that has been in her family for 75 years. She received her BFA in illustration from the Rhode Island School of Design and took additional classes at Boston University. She is frequently invited to exhibit her prints throughout Maine, and her children’s book illustrations are shown regularly at the Society of Illustrators in New York. Berry received an Individual Artists Fellowship for printmaking from the Maine Arts Commission in 2002. She is represented by Deer Isle’s Turtle Gallery.

Holly Berry works mostly in linocuts, which she treats fairly experimentally—carving textured linoleum, painting the carved block, and printing on different kinds of paper. Some of her prints become strikingly colorful and painterly. For actually transferring the inked design onto paper, Berry uses a rounded, custom-made piece of wood instead of a press.

The artist closely observes and sketches the natural world around her rural home, capturing the specificity of what she sees. In subsequent steps, she turns these original drawings into more universal designs. Intricately detailed backgrounds suggesting the animals’ environments display great variance in mark making and patterning. “Birds, animals, fish, insects, plants, and the planets all offer points of departure for me to explore, interpret, and integrate into my compositions,” Berry says. The artist has a great appreciation for the scroll work, interlaced patterns, and decorated borders of medieval illuminated manuscripts. Her contemporary updates include ornamental patterns and fanciful architectural structures that enclose the main designs.

Berry fully explores the strong linearity of relief printing to great effect. Yet preparing multiple blocks for a single image also allows her to print uninterrupted areas of color, as exemplified in her three renderings of Horseshoe Crab. The versions use different colors and numbers of blocks, thus allowing for expressive variations in detail and mood. The blue version illustrated here suggests an aquatic environment, and includes recognizable horseshoe crab anatomy, such as the animal’s carapace, pincers, and distinct outline. Yet Berry treats them like abstracted compositional elements and enlivens the overall arrangement with decorative patterning, while suggesting volume with white detailing. All three versions use the same unusual horizontal format. These particular prints began a more abstract phase for the artist, in which she has explored the surface of prints more than their content.

Holly Meade

Holly Meade received her BFA in painting from the Rhode Island School of Design but developed an interest in woodblock printing after attending a workshop at the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in 2002. Her prints have been shown at many galleries and art centers throughout New England, and several are in the collection of the Portland Museum of Art. Meade has illustrated more than thirty children’s books, some of which she also wrote. She was awarded two residencies by the Heliker-LaHotan Foundation and is represented by Courthouse Gallery Fine Art in Ellsworth.

Holly Meade lives in rural Maine, where she sees all kinds of fauna—“They rise out of my life,” she says. Yet animals are not her only subject matter, which also includes figurative work and scenes of farming and fishing. The artist maintains that she occasionally wakes up with an image in her mind “without knowing where it came from.” Meade thinks visually, and image, narrative, and autobiography often merge in her work. One can assume this in the depictions of an older woman comforting a younger one, the bouquet of flowers in a vase shaped like a female torso, and the print entitled Woman Dressed as a Mermaid Pursued by Shark Dressed as a Man. Meade describes her interest in creating images as “the desire to uncover the life beneath our lives, that dimension of spiritual integrity that I believe lives in each of us—an uncovering that will never end and never really uncover.”

Meade uses woodblock and linoleum printing, often combining the two to add color and compositional layering. Most of her work features a central scene or motif with little or no contextual background, but she sometimes purposefully leaves traces of the carving process to add texture and animation. Her line work is strong and bold, and her compositions give a measure of importance to the edges that convey an unstudied quality. These characteristics and her use of a red chop, or wooden stamp, of her initials pay homage to Japanese woodcuts.

In Porcupine, the rodent seemingly moves through the space of the print as if caught in mid-stride, surreptitiously turning its head to look at us. The fact that its tail did not quite make it into the picture, the lift of its front paws, and the direction of its quills, as well as the markings in the background, all support the illusion of a forward motion. While stylized, this delightful and humorous portrayal seems to capture the animal’s spirit perfectly.