Interstices: Found & Formed

THE CANVAS-January/February 2011

by Annaliese Jakimides

Katrine Hildebrandt, Sage Lewis, Daniel Minter

“A man’s real possession is his memory.

In nothing else is he rich, in nothing else is he poor.”

—Alexander Smith

Outward Circulation, 2010, cut archival paper and gouache, 21.5” x 28.5”

SLICING TO THE DEPTHS

It is both the philosophical and the physical that demand Katrine Hildebrandt’s exploration. An artist with a scientific eye, she calls it an “investigation.” A surfer, Hildebrandt believes that being out on the water connects her to “growth and energy patterns, both imagined and real.” And that connection to her work is visceral.

Outward Circulation is part of a series of cut-paper pieces “inspired,” she explains, “by natural cycles: accumulation, collapse, and creation.” As is often her process, Hildebrandt stumbled upon something. Often it is a shell, a pattern in the sand, a gnawed or distressed scrap of wood, but in this case, it was an old photograph of a northern Maine log drive. What drove her into the piece were “the way the circulation of the water aligned the logs,” and the question she could not abandon: “What will happen to those logs over time once the pressure of weight and water is placed against them?”

Of interest here in this natural world of cyclic energy is that the paper she uses is made from 100 percent recycled plastic, which allows “the wetness of watercolor to remain.” It also creates a subliminal philosophical commentary on the nature of nature.

She cuts with an X-Acto knife, typically changing the blade every twenty minutes. Although Hildebrandt’s background is in sculpture, she finds that working with cut paper enables her “to explore the world between the second and third dimension, becoming three-dimensional with the interaction of shadow and light.”

On the white walls of her home studio, she hangs “specimens”—things she feels compelled to hold on to. She has what she calls a “cabinet of curiosities.” Everything is neat and orderly except for the floor and the work tables, where ideas are allowed to simmer in chaos, waiting for their time—which always comes.

CONTRASTED SUBTLETIES

With paper, paint, and thread, Sage Lewis explores the structures that support our daily lives, which, she says, provide a constant study in contrasts. In each piece, looseness and precision, strength and weakness not only coexist, as they do in life, but are intentionally valued. Working in her studio in downtown Portland, she conducts “a lot of experiments where I discover techniques that sometimes lead to whole bodies of new work.”

Lewis says she did not come to use thread by way of an interest in women’s work, feminism, or a craft revival. “It is a way to draw with thread—to draw with a three-dimensional line…and a black thread produces a very satisfying line, not unlike an etching.”

As she does in Ink and Blackwork Doily, Lewis often uses ink and blackwork, a type of counted-stitch embroidery that became popular in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, to create abstractions of architectural forms—patterns symbolic of strength rendered with materials seen as weak and fragile.

Although most of her pieces are small enough to be stitched while sitting comfortably anywhere, larger pieces require a clothesline and a rolling chair for her to draw the thread from front to back.

She may lightly sketch out her pattern or “prick ahead,” working a couple of square inches at a time. She uses a ruler, but doesn’t measure, allowing the spaces to contract and expand. She chooses threads for their color, texture, and luminosity.

“I am often playing with optical perception, so the viewer may not be sure what is thread, what is drawn, or what is printed. Questioning perceptions of what may be strong or weak, reliable or tenuous in our daily lives is at the heart of the inspiration for this work.”

Ink and Blackwork Doily, 2006, ink and thread on paper, 6” x 8”

CALL & RESPONSE

Daniel Minter is a storyteller—with wood and paint, paper, wax, metal and stone, even old cardboard boxes. “I’m not in love with any material,” he says. “If I don’t have any paper, I work on wood. No wood, I work on metal. It doesn’t matter what I work on as long as I’m telling a story, as long as I’m talking to you.”

In every Minter piece, he is definitely talking—in a clear and compelling voice. Pieces of stories rise up and make themselves known. Even if you experience no immediate connection to the story, you get a sense of it. And that’s enough for Minter.

To him, that’s what creates community, and “without community,” he says, “there is no art. I don’t believe in art for art’s sake.”

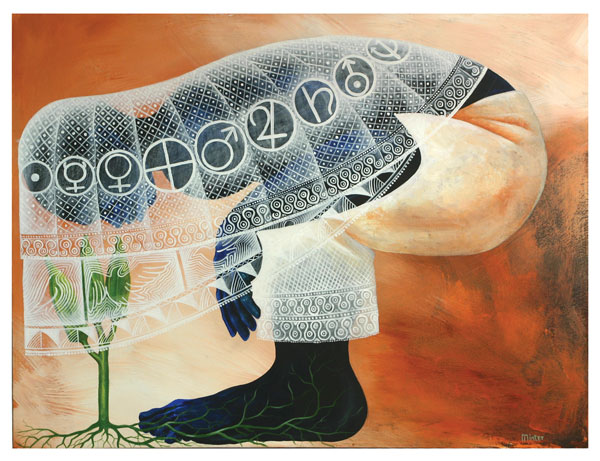

“I’ve done some pieces similar to Oxala before, and they’re always like a prayer. Oxala represents peace and light, a force of nature that always knows right from wrong, to a fault. He is not perfect, but he is seeking perfection.”

Minter works in a studio that fills the top floor of his house in Portland, not to mention the garage and the basement. “I work in the kitchen, too,” he says. “I like sitting around other people when I’m working.”

His mornings are filled with detail work: a design problem or block carvings that will be used to illustrate a children’s book. “That’s when I’m still willing to sit and think.” In the afternoon, he works on something more active. And whenever he goes out, he brings a sketch pad and a carving tool.

Minter has no idea where he is going at the beginning of a piece. There is “only a concept or a feeling,” he says, “and the last piece I did. The last piece always finds its way into the next. It still has something it wants to say.”

Oxala, 2009, acrylic on canvas, 16” x 24”