Always Summer: Preserving Maine’s Historic Painted Walls

The Center for Painted Wall Preservation is working to save a forgotten 19th-century American art form—murals that bring New England landscapes indoors.

There were many ways for a wealthy family in the 1800s to signal their status at home, from serving celery in designated vases to displaying gilt-edged mirrors in the sitting room. For New Englanders, it was a time of relative prosperity, with goods arriving from all over the world to their bustling port cities. But there was one homegrown status symbol that has largely been forgotten and ignored: the practice of painting walls.

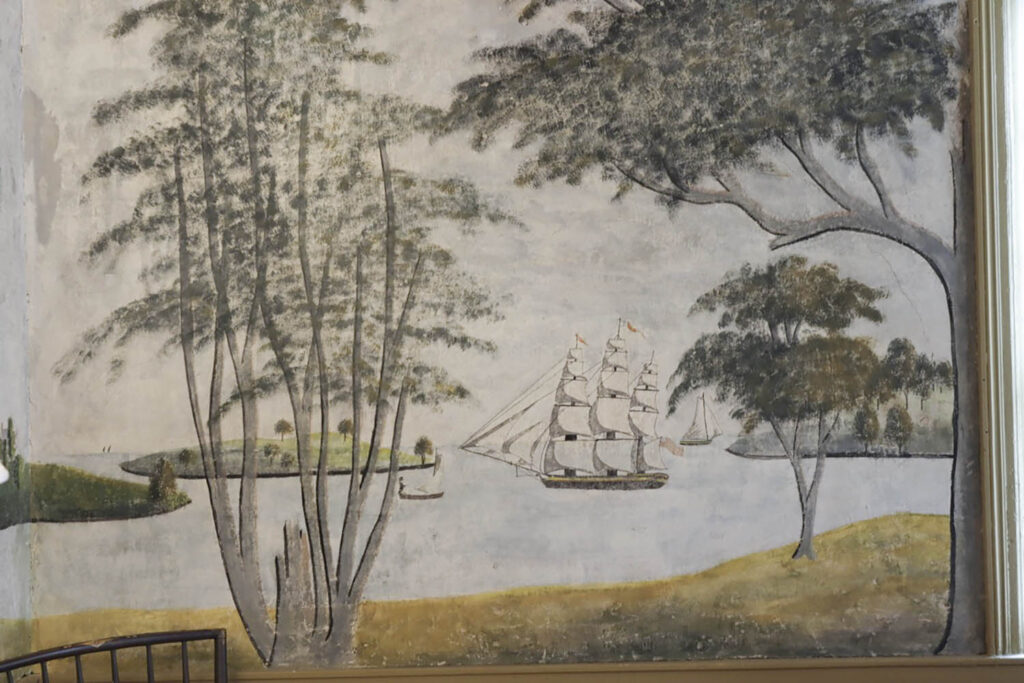

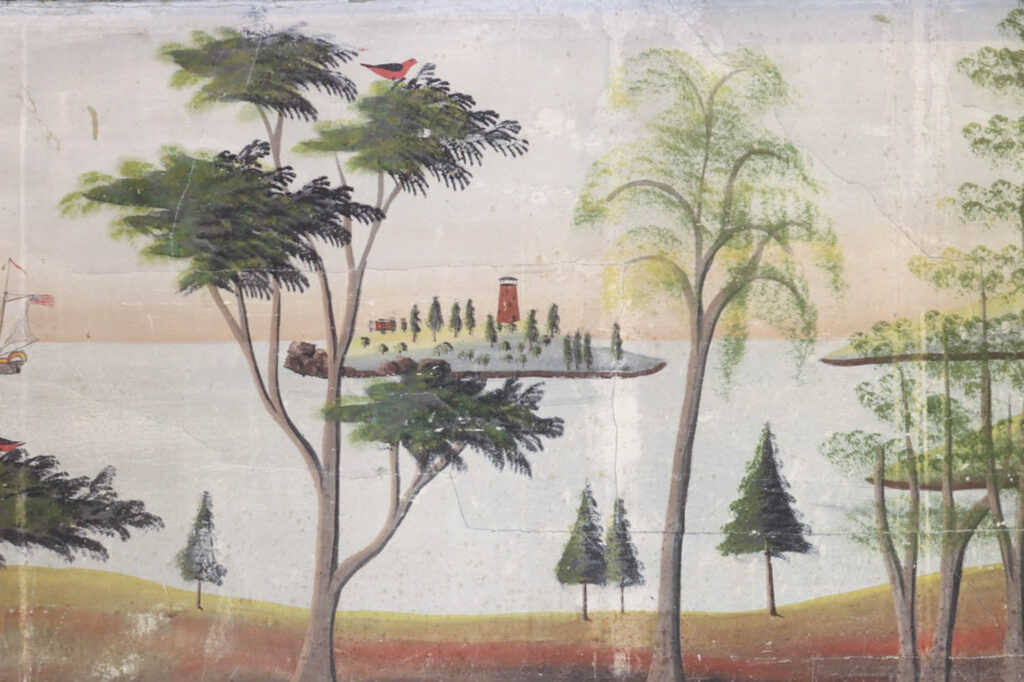

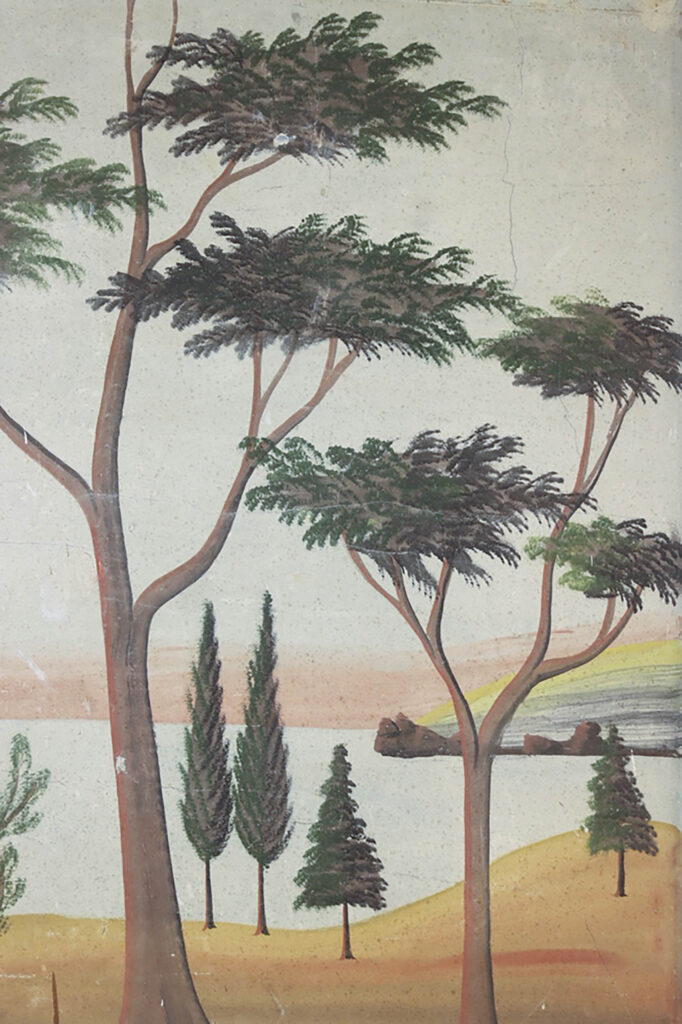

Murals have existed since time immemorial, but there was a distinct style of naturalistic, intricate scenery that decked the halls of upper-class homes in Maine and its southern neighbors. They featured farmsteads with apple orchards, and harbor scenes with both working and pleasure vessels. While they could be placed anywhere in a house, most were completed in entryways and going up the stairs to the second floor. Sometimes they were installed in bedrooms. “And it was always summer,” says Hallowell-based historian Jane Radcliffe. “Never winter.”

Radcliffe has been researching, cataloging, and preserving this folk art form since 1971, when she first came across a crate filled with deconstructed walls at the Maine State Museum, where she worked as a historian. “I’ve been at this awhile,” she laughs. As a young art historian, Radcliffe was drawn to the whimsical details and careful brushstrokes that mark the murals. She quickly came to believe that these weren’t stenciled or mass-produced, but works of art created by talented local painters, including Rufus Porter and his nephew, Jonathan D. Poor. Word began to spread among her colleagues that Radcliffe was interested in these decorative pieces, and over the years her project gained momentum. She met other historians and began collaborating with them to protect and document the walls. In 2011 Radcliffe coauthored a book on the Porter school of landscape painting, and in 2015 she cofounded the Center for Painted Wall Preservation with a group of fellow historians and antiques dealers. Their organization recently created the Virtual Museum of Painted Walls (accessed through their website,

pwpcenter.org). The online museum consists of the digital archive, documenting over 400 locations throughout New England and New York State with thousands of digital photographs, as well as 20 immersive tours using Matterport technology. “You know how real estate agents use that tool that lets you go around the room and zoom in?” Radcliffe asks. “It’s like that. You can go in, move around the room, and there are red dots where you can home in on a feature and get more information about it. We’re excited.”

After spending decades examining this short-lived art form—the heyday of painted walls in Maine was between 1820 and 1840—Radcliffe has developed some theories about how they were created, who made them, and why. “People often think it was a cheaper option than wallpaper,” she says. “But I’ve looked at the numbers, and I don’t think that is true.” According to Radcliffe, the reason people commissioned this form of decor had less to do with the cost and more to do with preference. At the time, wallpaper imported from Europe tended to be geometric and brightly colored (easily mimicked by stencils) or to show scenes of European life and farming. In contrast these painted walls showed visions of America—an idealized, pastoral version of New England, where every town center was perfectly charming and every church steeple perfectly pointed and every harbor bustling and full—but New England, nonetheless. “These paintings were a very early form of American landscape painting,” says Radcliffe. “They showed things you could see if you looked out your window.” She relays the story of one elderly woman who was confined to her room for several months, which led her to realize that the painted wall across from her bed wasn’t just an imaginary scene. “One day, she looked out the window, and there was the same tree,” Radcliffe says.

In some ways Radcliffe is a champion for the underdog; these murals weren’t considered fine art, and many of them were likely lost to development, time, and weather. “I think it’s much more widespread in New England than most people think. We’ve documented well over a hundred houses in Maine.” She continues, “While some of them are very formulaic, leading people to assume they’re stenciled, I think Jonathan Poor painted mostly freehand.” Porter is perhaps the better known of the pair—most likely because his stylized and formulaic murals are easy to recognize—but Radcliffe tends to prefer Poor’s work. “Porter’s don’t have a lot of what my coauthor used to call ‘extraneous detail.’ But Jonathan D. Poor had a great sense of whimsy to go with his realism,” she says. One mural that is currently on display at the Rufus Porter Museum in Bridgton was painted by Poor in 1840 for Lorenzo Norton in East Baldwin. It features small oddities like a clothesline with laundry hanging on it and piles of dung sitting outside a barn. “Poor often put in little hunting scenes, like a man shooting at a bird that was much larger than him. One has an eagle in the air with a songbird in its mouth,” she says. “There’s so much to see.”

“I think a lot of times, people . . . had gotten tired of having white walls—that’s how the whole thing started, I think.. They started with whitewash. Then they added color to it. Then, why don’t we put some sort of design on there?” muses Radcliffe.

Created with distemper, an early form of whitewash that used easy-to-carry dry pigments mixed on-site with glue, these paintings hold their colors fairly well. As for why so few people seem to know about this art form, Radcliffe speculates, “I think they were done in private homes, and by the time the Victorian era came along, I think people were embarrassed to have these naive American paintings. They wanted to be more fashionable and go with more European stuff.” Some of the murals have been preserved because they were covered over with flocked wallpaper and other period-trendy decor.

“We’re still finding new ones,” she says. “Fortunately, I think people are becoming more aware of them. Our hope is that, when people buy an old house and go to renovate it, they will try to look under the wallpaper before they paint over it or tear down the wall.” Radcliffe has advice for anyone removing wallpaper from their centuries-old home: “Go very slowly, and carefully.” There might be a piece of Maine history hiding behind that faded paste-up.