Returning Home

After a flood, an artist repairs and rethinks an old farmhouse

A brutally cold winter and a late oil delivery—one plus the other equals bad news, and in January 2014, that bad news fell on the ears of Richard Lane of R.A. Lane Construction. He received a handful of phone calls from people who noticed a giant slick of water—or what some described as an expanding iceberg—in front of Elmwood Farm, the Camden property owned by artist Amy Lowry, who at the time commuted between Chicago and Maine. Lane knew the house with its ell and attached barn well. Between 2009 and 2011, he’d worked on a minor renovation of the house, and with the architecture firm Scholz and Barclay Architecture, on a major renovation of the oversized barn. The latter was reconfigured as a garage space and artist’s studio on the ground floor and a possible event space on the second. This involved structural work, including jacking up the barn and pouring a new foundation, replacing the windows and siding, repairing the cupola, and adding a balcony, which offers beautiful views of the back lawn, nearby woods, and hills. Now Lane had a considerably less desirable job. He called plumber Tim Hall of Seacoast Plumbing and Heating, and the two made their way over to Lowry’s house.

What they found was a disaster: water spraying out from a pipe under the kitchen sink, the living room and family room ceilings collapsed onto soaking furniture, pink insulation spilled everywhere. The two men didn’t even try to walk into the basement; it was full of water.

If Lowry’s next renovation plans had been focused on completing the second floor of the barn, she now had more basic work to do, all of which, she says, she found physically and emotionally wrenching. She started to commute regularly to Maine to oversee the process. Lane was overcommitted for the season, far too busy for what the house needed, which was everything, so his colleague Robert Staples, a carpenter from Warren, stepped in, stripped the house back to its studs, and started rebuilding.

There were standard complications—proliferating mold, the insurance company’s low repair estimates—and the bigger complication of retaining the house’s original historic character while allowing it to be what it had been all along: a showplace for Lowry’s creative, eclectic, busy mind.

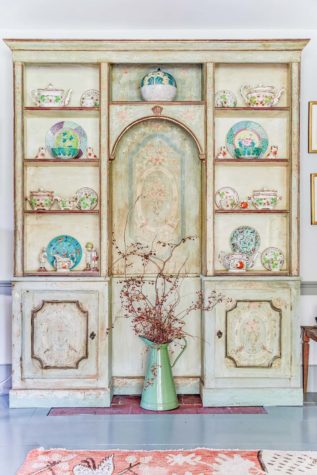

Lowry is a painter and children’s book author, as well as a maker of objects, collector of art, assembler of curiosities, frequenter of flea markets, and inheritor of antiques. She owns the work of major American artists, three of whom—Tom Wesselmann, Will Barnet, and Duane Michals—Lowry modeled for when she lived in New York in her 20s, and some of whom have Maine connections, such as Joyce Tenneson and Tom Burckhardt. Lowry’s house and studio are full of antiques, paintings, photographs, art books, and wooden boxes whose cubbies are filled with items like a plastic doll’s head, a turtle shell, an antique insect repellant container, and other oddities. Her possessions inspire wonder and questions, all invariably rewarded, as so much of what is in the house comes with a story. An early American painting in the dining room once hung in Lowry’s sister’s childhood bedroom, and the family nicknamed it “The Sour Girl.” Mosaic cakes that Lowry made out of broken china, using a technique called pique assiette, appear throughout the house; they employ cheerful decorative colors, but their visuals reference global warming, war, and similarly dark matters. A large, playful grasshopper illustration in the kitchen was created by Lowry when she was in China. (Lowry bought the farmhouse with her former husband in 1991 to serve as a home base during their four-year stay in Beijing for his job.)

Elmwood Farm was built in the late 1700s by a lumberyard owner as a gift for his wife. “The story,” says Staples, “is that he never gave her any gift worth more than five dollars after that.” As one might suspect of a house built at that time, the structure had plaster and lathe walls, posts and beams made from the region’s king pines, fireplaces in most rooms, and wide pine floorboards. Sadly, four dumpsters’ worth of this material ended up in the trash before renovation could begin.

For an outsider visiting the house in 2018, there’s no evidence of damage. If asked to identify what had been added, one would likely mention the swimming pool and stone hot tub outside, the ground-floor bathroom (which incorporates Lowry’s pique assiette in the countertop and shower stall), and parts of the kitchen, such as the slate floor. Upstairs, one bathroom was converted into two. Otherwise, you’d believe the rooms to be original, especially given their period fireplaces, dark paint colors, and wide pine flooring. “He pulled my home down and put it back up,” says a clearly grateful Lowry of Staples.

As Staples was tossing wood into dumpsters in the early stages of the repair, Lowry found herself climbing in to rescue a few of the boards that interested her. Layered with paint, they struck her as full of history, and Lowry was already invested in working with the past. For years, her grandmother ran a well-known antique store in Camden. “Antiques are in my blood,” Lowry says. (They are part of why she favors pique assiette for her cakes. She likes to get history—old china, in this case—into her artwork.) Lowry hung three of the salvaged boards on her studio wall. One night, when the moon was full, and she was drinking cognac, Lowry says, she looked at the boards and saw images suggestive of water and land. Instead of working on blank canvas, as she naturally had in the past, Lowry began to paint on these boards, incorporating the shapes she saw. One piece of wood had a bit of red paint, which suggested a buoy, helping Lowry to realize her new work was “about safety, returning to safe harbor.” The still-evolving series—called Red Right Returning, the nautical phrase for keeping the red buoy to starboard when returning to shore—will eventually incorporate text, offering the metaphorical narrative of what happened to Lowry after the flood, as the upheaval at the house paralleled an upheaval in her life. Both brought about her decision to live in Maine full-time.

Right now, the panels for Red Right Returning fill the center of one wall of Lowry’s studio. But Lowry always jumps from project to project, and that is not the only work space in her studio: In a different area, she assembles her memento boxes. In another, those boxes hang. One has doll parts sticking out of coral. Another, a predatory monkey/lizard creature. On one wall, Lowry has hung work by her daughter, Nina Poole: black-and-white minimalist photos covered in encaustic. Multihued flat file cabinets are painted with the same vivid chalk paint that Lowry used for an armoire (built by Staples) and freestanding silverware cabinets in the house. At the center of the room is a low round table with an unfinished Scrabble game, a reminder that things are in process in this room. And that’s all for the good. Lowry’s next project is to develop Elmwood Farm as a space for workshops, salons, and other events—a beautiful property where, as she says, “artists, chefs, writers, musicians, environmentalists, healers, creatives in any medium can gather to collaborate, entertain, hold fund-raisers, share ideas, teach, learn, and be inspired.” A place where unmade things can be made.