Craft in Architecture

AIA DESIGN THEORY – August 2012

Edited by Rebecca Falzano | Photography Trent Bell

Architect Will Winkelman on craft

Craft, the physical manifestation of design, is an indispensable part of architecture. Will Winkelman explains why.

There is a deep and rich tradition of craft in the history of architecture. It is an indispensable part of the work of many great architects, past and present, notably Frank Lloyd Wright, Alvar Alto, Carlo Scarpa, William Morris, and Charles and Ray Eames. And while there may be a preconception of crafted works being identified with older buildings, many contemporary architects wholeheartedly embrace this approach as well. Check out the work of Tom Kundig of Seattle and his mechanical, beautifully textural creations using steel, concrete, and glass. According to Will Winkelman of Winkelman Architecture, it is the integration of this added layer of “craft”—of touch, texture, art, and detail—that adds so much to how a building lives and is experienced. “It can add an entirely new dimension,” says Winkelman. “But in recent times, it seems to be more of a forgotten art.” MH+D asked Winkelman to elaborate.

Q: Isn’t craft in architecture a collaborative process—one that depends heavily on the craftspeople involved?

A: As a practicing residential architect, I have had the opportunity to work on some hopefully artful and crafted creations. In doing so, I’ve learned how ideas are nothing without the ability to give them shape. And therefore, it is the contribution and skill of the craftsperson that is essential, as a partner and a collaborator, in the process. Taking part in this process gives one a fresh perspective when looking at some of the incredible creations in our past. Look at the work of Antoni Gaudi (and his cadre of craftspeople) and the blend of artistry, detail, structure, textures and mechanical operation. No CAD software, no CNC machines, not even photocopiers—just imagination, an incredible skillset, and clearly a dialogue based on trust and respect. Hopefully, it raises the bar for the things we attempt to create today.

This may be an odd analogy, but sometimes this process can be like cooking: if you have the right ingredients and the right cooks, the outcome will be tasty even if it was not overly prescribed to start. And thus, the key is to bring the right craftspeople to the conversation and identify the right materials to work. The outcome might not be the initial preconception—it might be better. Designers in Maine are fortunate. Our state has attracted and nurtured artists and craftspeople with deep and varied skillsets, from boatbuilding to furniture making, to metal working to paint and fabrics. This has created an incredible resource pool of craftspeople and artisans with whom to work and learn from.

Q: What about the number of other architectural considerations that go into play?

A: Architects speak of the importance of “detail,” and rightly so. Thoughtful detailing is essential for proper attention to weather, structure, longevity, maintenance. But tending to this proper resolution can sometimes be a crutch, a standard or common solution. But if we can keep that detail-oriented conversation alive, and nurture it and further it and with an open ear to the various hands in play, then so much more can come of it. The addition of a layer of craft to a project furthers the project’s narrative, giving more depth and character, furthering the story of its “place.” Sometimes it can be simple injections, such as reimagining the use or assembly of something ordinary in a unique, inspiring way.

Q: How can architects be more connected to craft in their work?

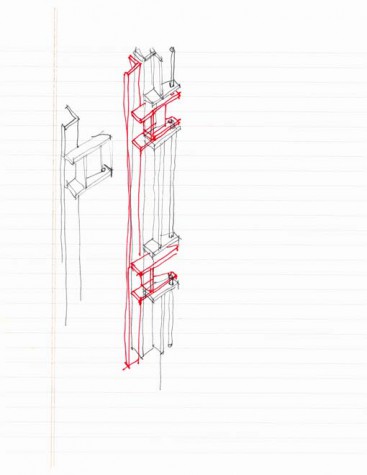

A: It can help architects if we get our hands dirty; if we try to “make” a few of these things we design. While this is true for big things like houses, additions, or renovations, it very much applies to these smaller things too—like cabinets, sash, hardware, lighting. Some of these delightfully textural, intriguing, and sometimes complicated things can look so simple but can be maddening to try to make. The experience can be humbling. It can teach us about the nuance of working with certain materials and offer us an appreciation for the skill and competence required. It can also shed light on how much time is really involved in making some of these things. And thus it informs us about the real world time these things might require to make, reflecting on appropriate cost and value as well.

Q: What tools does an architect have at his or her disposal?

A: Consider for a moment architecture itself to be a craft. Our medium are the intangibles of volume, form, light, surface, place… and our tools, beyond ingenuity and the ability to draw, are the skilled craftspeople with whom we collaborate, manipulating the wood, steel, stone, and glass into our shared creations. Such an attitude might help nourish a deeper place in our work and keep a connection with the crafts. Together, architects with their collaborators endeavor to create something that is more than the sum of its parts.

For more information, see Resources on page xx.

American Institute of Architects

Maine AIA: 207-885-8888, aiamaine.org

Winkelman Architecture: 207-699-2998, winkarch.com