Heroic Acts: Grace Hartigan’s Early Collaborations with Poets

At the Portland Museum of Art, Grace Hartigan’s groundbreaking works reveal how poetry shaped her bold path between abstraction and representation.

The era of the exhibition Grace Hartigan: The Gift of Attention is 1952 to 1968; the setting is New York City. Establishing a chronology of Hartigan’s early works is crucial to the experience of the exhibition as a whole, since the works trace her intimate artistic collaborations with major poets of the New York School, including Frank O’Hara, James Schuyler, James Merrill, Daisy Aldan, and Barbara Guest.

Grace Hartigan (1922–2008) was 30 in 1952. Three years earlier, she’d seen a Jackson Pollock exhibition that “hypnotized” her, prompting a rebellious, career-making decision to abandon her marriage and child in order to paint every day. In 1952 she made a painting, Persian Jacket, that would be acquired the following year by Alfred Barr, then director of the Museum of Modern Art. She was deeply embedded in the Cedar Tavern scene, where the prominent avant-garde writer and art dealer John Bernard Myers hosted salons to connect emerging New York School painters like Hartigan, Pollock, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, and others with the New York School poets.

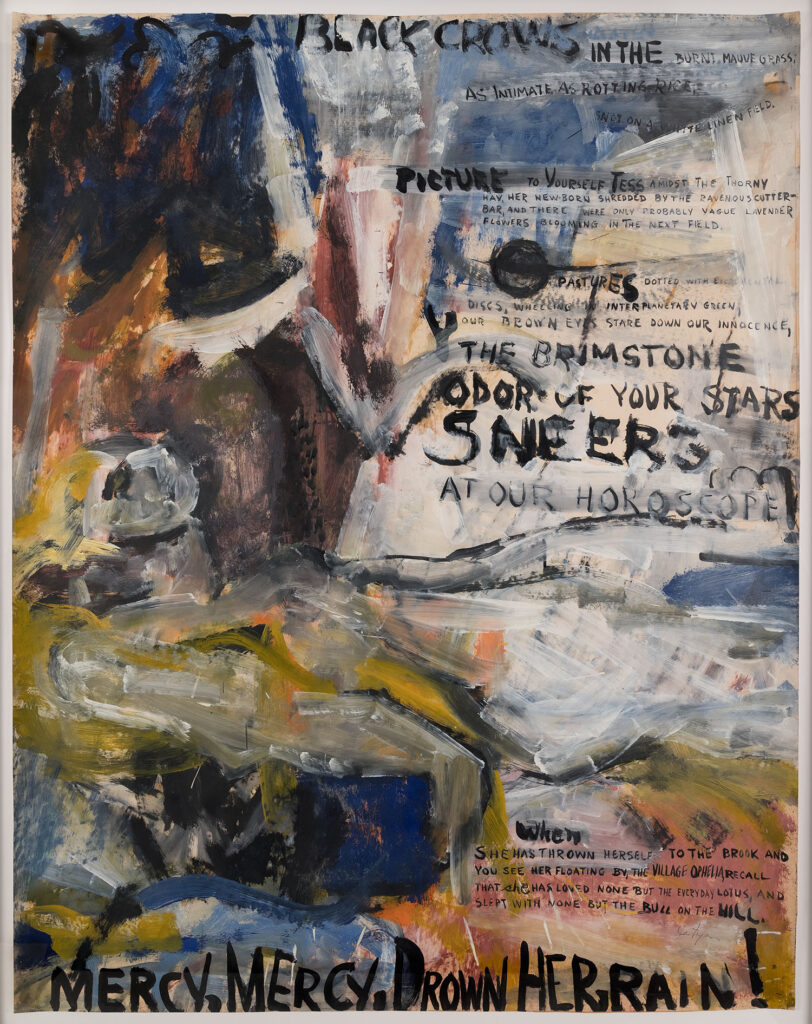

It’s likely that Hartigan first met Frank O’Hara at the Cedar Tavern, and that their first collaboration, Black Crows (Oranges No. 1) from 1952, was “more of a dare,” says North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA) curator Jared Ledesma. O’Hara provided Hartigan with poems he’d written in college, and she responded boldly in paint, using affordable materials at hand: newsprint and house paint. She began by inscribing the text of the O’Hara poem, “Oranges I,” onto the newsprint, and then “image making” around the words.

As Hartigan’s painting language sought to move fluidly between abstraction and representation, she rejected artistic mandates of the time, especially those exalting pure abstraction. Finding common artistic ground, encouragement, opportunities for collaboration, and even patronage among the New York poets was so important to Hartigan’s development and endurance. The poet James Merrill, son of the founder of Merrill, Lynch, and Company, funded major museums’ acquisitions of Hartigan’s work, including Interior with Mexican Doll (1955), by the NCMA, East Side Sunday (1956), by the Brooklyn Museum, and Grand Street Brides (1954), Hartigan’s enormous oil on canvas inspired by her beloved Velazquez, which Merrill helped purchase for the Whitney Museum of American Art. As Ledesma so beautifully articulates in the exhibition catalog, Merrill and other poets offered Hartigan “unequivocal endorsement—their gifts of attention,” and Hartigan benefited creatively, emotionally, and financially.

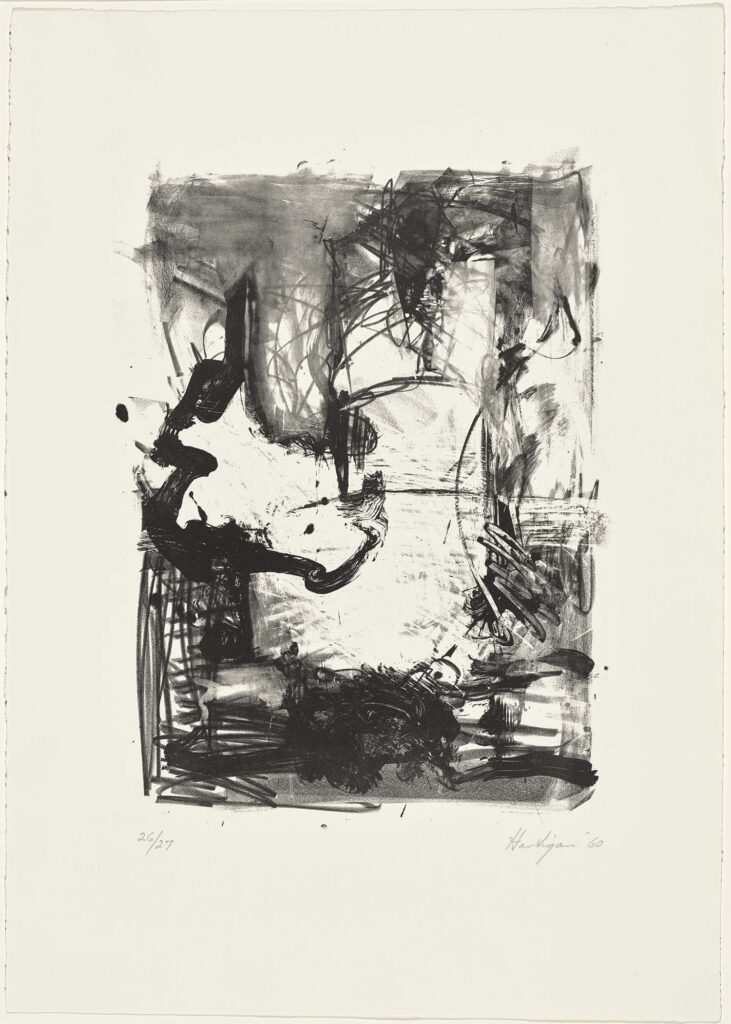

If Hartigan’s work with Frank O’Hara is one bookend of the exhibition (and this period of meaningful collaborations with poets), her work with Barbara Guest is the other. Guest and Hartigan began a friendship and correspondence in the late 1950s. Through the early 1960s, Hartigan responded directly to Guest’s poems in paintings, collages, and notably, lithographs. Hartigan had never made a lithograph (a complex printmaking process) before she embarked on a series of gorgeous tonal grayscale prints inspired by Guest’s poem, “The Hero Leaves His Ship.”

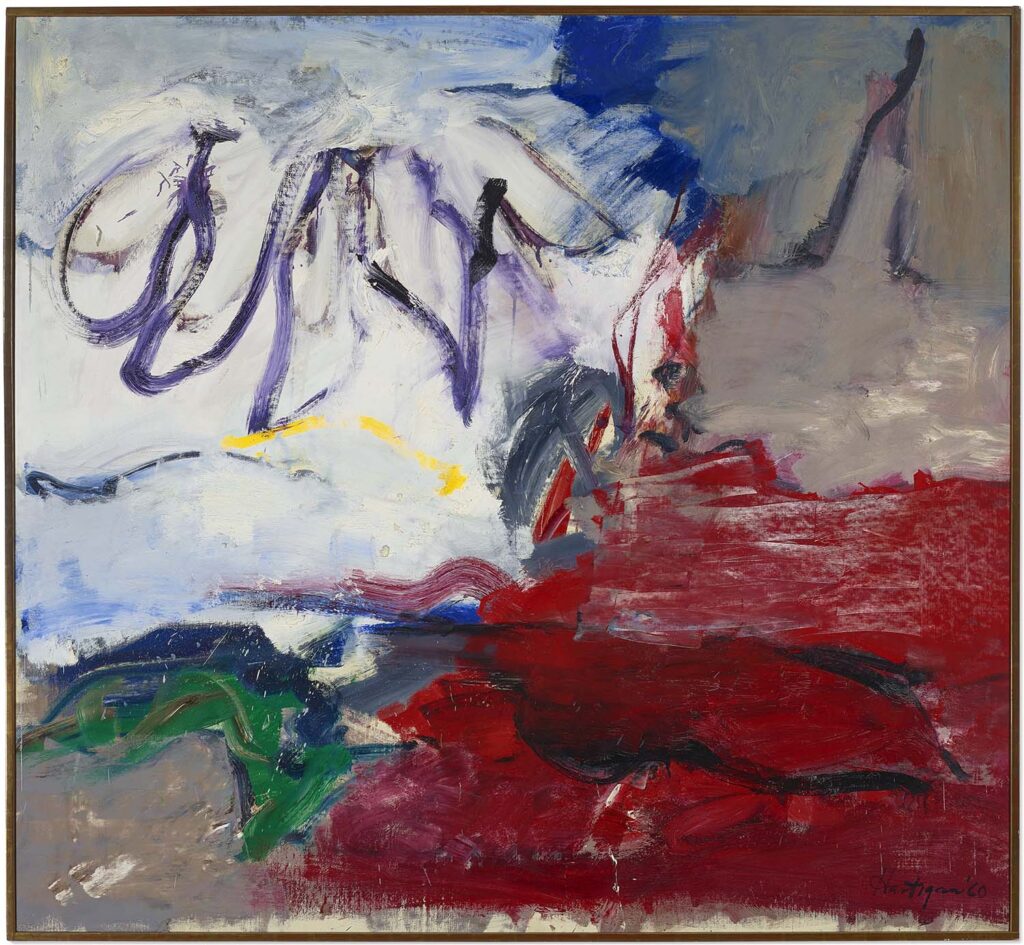

Hartigan’s oil on canvas, The Hero (1960), also in collaboration with Guest, would be her last New York painting. Though Hartigan continued to work and correspond with Guest for several years after making a move to Baltimore, leaving New York meant leaving behind a remarkable, irreplaceable camaraderie.

“No one was known, there was no fame, there was no money, there was no power.

—Grace Hartigan, describing her early years in New York City, in a 1990 lecture at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture

They were just artists, doing this far-out thing that they just took for granted. It came out of existentialism and the disillusionment with World War II, and the feeling that there

was nothing in any society or in any nation or in the world to believe in. They felt the artist alone represented mankind and the loneliness and the alienation, and that the most heroic act was to face a blank canvas.”

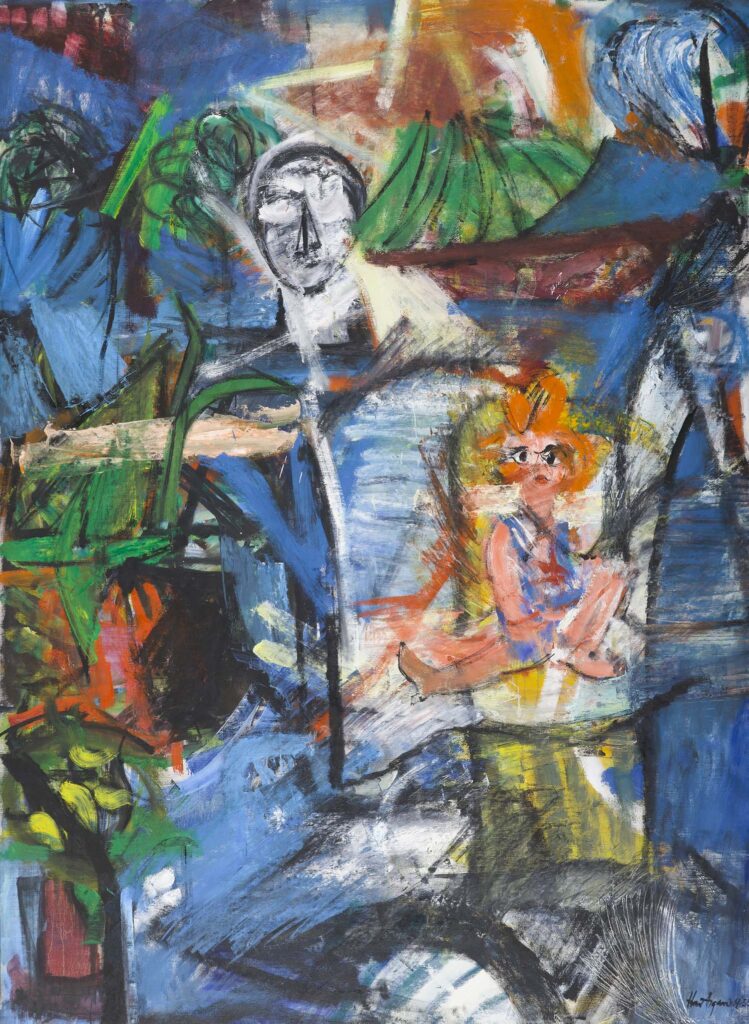

“Hartigan had a career that developed in many stages,” observes PMA Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Sayantan Mukhopadhyay. Mukhopadhyay brought the exhibition to Maine in collaboration with Ledesma and the NCMA, adding two late oil paintings from Maine museum collections: Ophelia, 1996, on loan from the Farnsworth Art Museum, and the PMA’s own Don Quixote and Madame Butterfly, 1986. “These two works are presented as a coda to the exhibition. Here, Hartigan continues her interdisciplinary journey through literature (and opera) to painting, however the figure in these images comes forward—no longer blurred through the techniques abstraction.”

Grace Hartigan: The Gift of Attention is organized by the North Carolina Museum of Art and will be on view at the Portland Museum of Art from October 16 through January 11, 2026.