Anne Gable Allaire: Heartfelt Art

PROFILE – June 2014

By Penelope Anne Schwartz | Photography Irvin Seranno

Pastel artist Anne Gable Allaire is inspired by the world around her

Kennebunk artist Anne Gable Allaire grew up in Missouri and Iowa. When she was nine, her parents encouraged her early interest in art and sent her to the Des Moines Art Center for lessons. Allaire remembers being overwhelmed by the Eero Saarinen–designed building, but inspired by the smell of oil paint. “It got right into my bones,” she says. At the University of Nebraska, she earned a degree in fine art, painting, and interior design, adding the last in deference to her parents’ concern she would not be able to support herself by painting. It was a wise choice, for her career in commercial interior design took her to Minneapolis/St. Paul and Detroit, where she worked first for an architect and then a design firm. During that time Allaire worked on projects that included the lobby for the World Trade Center and clients such as the Washington Post and Ford Motor Company. When she relocated to Maine more than 30 years ago, her artistic values were seasoned and experienced; more, they were open to what she calls “wonder,” the sense of awe “and amazement at the beauty around me.” She elaborates, “Sometimes that might be the natural world or an interior space that invites me in. I hope to share this sense of wonder with those who view my work.”

Allaire mentors MFA candidates at Heartwood College of Art and also gives pastel workshops. In addition to attending to the business of art, she paints about four hours a day, preferring to work “in place,” most often en plein air. Some of us who aren’t artists have a notion of a person before an easel on the shore, layering in sky, sea, rocks. “The first thing I do at a site,” Allaire explains, “is to tune in to the feeling of a place and determine a focal point from that spot. Then I establish a composition based on the values, or relative lightness or darkness of things. I first must establish a sound composition based on a good value structure.” This commitment to establishing values and composition en plein air allows her to then complete work in her studio based on those value studies and preliminary color sketches. Value in painting is more important than color, or hue, which may distract a less professional artist. The practiced artist begins by removing color from the equation. An artist who doesn’t get her values right may produce the equivalent of visual noise.

Harmony is the essence of Allaire’s work, which has won numerous awards. I am struck, in the small gallery of her Kennebunk home, by the impact of several paintings in which the figures appear with their backs to the viewer. In one, Wonder, a toddler (Allaire’s granddaughter) in footed pajamas has pulled aside a curtain to peek out a window. We don’t need to see her face in order to realize her emotion, as sunlight pours around where she stands in a darkened room. Another painting depicts two of her grandchildren standing at a railing, overlooking a marsh and sweep of green meadow. Their posture—the way their feet are placed and the way their bodies lean both forward and into one another—inform us this is a special moment of shared experience. We are invited more fully into these paintings by what is omitted; obscuring the faces allows us to imagine rather than be directed. This technique eschews sentimentality.

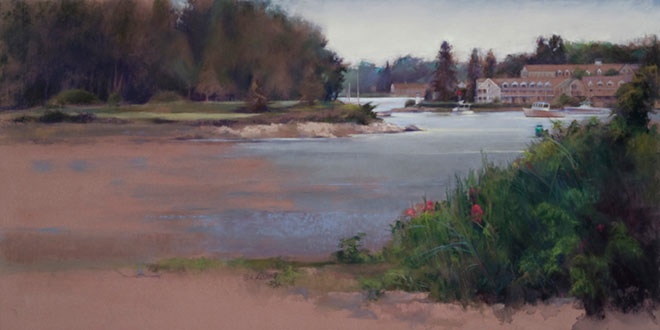

Allaire’s landscapes and seascapes are also technically and emotionally impressive, characterized often by skillful chiaroscuro, the effect of contrasted shadow and light, with the latter falling unevenly or from a particular direction. Among these are Coming Home, a glimpse across a river to the Nonantum Hotel and Kennebunkport beyond, and Narragansett by the Sea, a dramatic vision of dark sky and glowing water illuminated by a finger of light from above. The former painting won Best in Show in the 2010 Art Guild of the Kennebunks Annual Awards Show, and the latter was featured in the Pastel Painters of Maine’s 13th annual International Juried Exhibition for Pastels Only in 2012.

Two works in her Franciscan Monastery series, Inspiration I and Solitude I, beautifully capture the quiet spirituality of place in shifting woodland light. The Franciscan Monastery on Beach Avenue in Kennebunk is one of Allaire’s favorite places to be. “Mostly, I go there and paint. Sometimes I go there just to sit and soak up the atmosphere. It’s a very healing place.” Healing has been an important aspect of Allaire’s life in recent years. In 1997 she was diagnosed with a medical condition necessitating radical procedures. She underwent a heart transplant and a stem cell transplant within less than a year of each other. Waiting for her heart involved nearly three months of hospitalization. “I took great comfort,” she says, “in the fact that I was in a Franciscan hospital. I painted the whole time I was there. That’s what kept me going.” I ask Allaire what she was able to paint from her place in one room. “There was a tree outside my window,” she smiles. “I just kept painting it, every day a different way.” Although she doesn’t say so, it’s evident this extraordinary experience transformed her, that her art is truly heartfelt. “There is more to my story than those medical challenges,” Allaire says today. “I have been helped to strengthen my artist self and to continue healing by just showing up, doing the work of my art, and feeling the energy produced by the combination of process and place.”

Pastels are Allaire’s passion. Unlike a painter’s palette, the sticks consist of pure color—powdered pigment—with a minimum of binder. She began using the medium when she was 12, and is delighted that pastels are now having a renaissance. A juried signature member and a designated master pastelist of the Pastel Society of America, who has previously worked in oils as well as pen and ink and pencil, Allaire now works exclusively in pastels and believes pastel painting is a perfect combination of painting and drawing, which “allows my creativity to flow.”

Allaire’s work has been exhibited in the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio, and the National Arts Club in New York City. Her work is currently being exhibited in the Maine Arts Commission’s Art in the Capitol series, March 10 through June 2. Allaire is delighted to have been chosen, because Maine is her adopted home and she considers it an honor to have the opportunity to exhibit in the State Capitol. Moreover, her show will be the first in the “Art in the Capitol” program that features pastels. “Pastel is the oldest and most durable medium, and I am excited to think that this show may bring more awareness to the endless possibilities of this beautiful means of creative expression,” she says. “Although I also do figurative work,” Allaire continues, “I have selected a collection of Maine landscapes and seascapes for this exhibit. I want to highlight the beauty I see in some of the very special places where I live.”

Visit Anne Gable Allaire’s website for more information: agafineart.com.