Keeping it Loose

AIA DESIGN THEORY – May 2013

Edited by Rebecca Falzano | Photography Matt Cosby

Architect Dave Johnson on the informal beginnings of a design.

Dave Johnson of Skaala grew up building tree houses and rafts around his family’s home. One day his architect father got him a job working on a project for a builder. “He pretty much dropped me off and said, ‘Here you go, see you at five,'” recalls Johnson. It was a cold awakening to the job market, but one that showed Johnson the reality of a sketch he had drawn for his father earlier for that same project. “It gave me a greater understanding of the physical construction process and an appreciation for what the craftspeople in the field are going to do when you draw that crazy, creative detail on paper,” he says. For an architect, it takes great care to balance a sketchy poetic inspiration with the urge to make the details taut and real, but often it’s in this early “squint-your-eyes period,” as Johnson calls it, where the design magic happens. We asked him to tell us more.

Q: WALK US THROUGH THE INFORMAL, EARLY STAGE OF DESIGN. WHAT HAPPENS HERE?

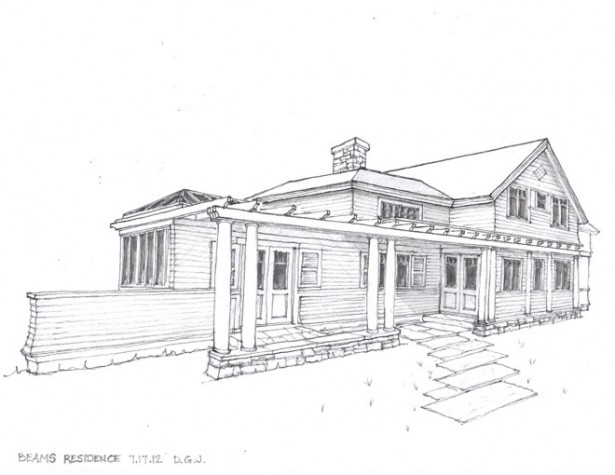

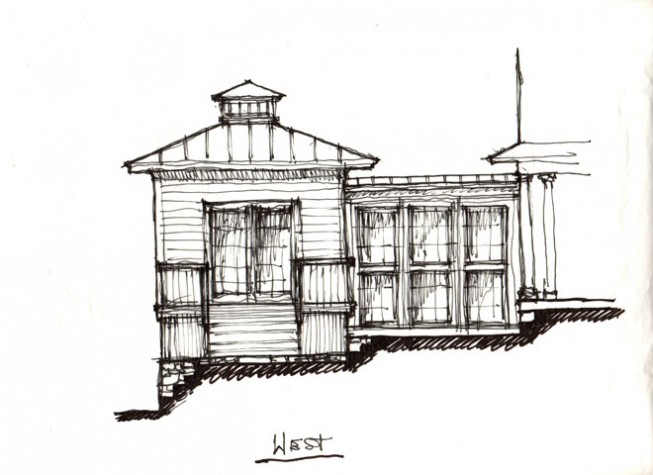

A: We begin all projects spending time with the site. Forging a connection to the site—its natural light, prevailing winds, and geographic features—is paramount. We seek to divine that intimate connection with the character of the microenvironment, looking for idyllic and pastoral views, considering the local vernacular, borrowing materials from the given site, and always searching for the sun. It all starts very informally—freehand, fat- pen sort of sketching that lets subconscious energies flow. In the end it will all get developed into a few schemes for review, but the early “squint-your-eyes” period is critical. The site, sun, and surroundings have a way of providing appropriate responses when we allow ourselves to respond intuitively. Drawing freehand early in the process, without the precision of CAD or other computer programs, helps keep it all loose. We put the pen to paper and let it almost have a mind of its own. All the guidelines are there: the property lines, the height limits, proximity to water, etc., and we hold them all in our mind’s eye, but the flow of free-form sketching reacts to the lines of site-derived energy and elements.

Q: WHAT IS AN EXAMPLE OF A PROJECT WHERE THIS FREE- FORM SKETCHING WAS ESPECIALLY FRUITFUL?

A: On a recent project with a lot of grade change and very directed views we sketched how the site suggested a home could sit within its context. A bowl-like topography and tapering view channel resulted in a multiform design, allowing it to shift and rotate with the contours and toward the views. Physical brainstorming like this is a fabulous exercise, requiring a completely open mind and the ability to always ask “what if?”

Q: WHAT TRENDS ARE YOU SEEING IN DESIGN TODAY?

A: We live differently today than we did a hundred years ago. Many people spend more than three quarters of their waking hours in the kitchen or nearby, no matter how welcoming we make other spaces. That results in the common request for an open floor plan. Today we have different technology and a far greater understanding of the consequences of our actions. One consistency, though, is the profound responsibility to respect the smart things that our predecessors did and the beautiful houses they created. A far greater challenge is creating structures worthy of that same respect from future generations, while remaining firmly rooted in “the now.” I’ve been stimulated by a clientele who embrace an architecture that responds equally to their needs, the site’s given individuality, the neighboring architectural context, and our ever-improving knowledge of building science. We are in a very unique position of being both pragmatist and artist. Pragmatically, the structure has to function. Artistically, it has to stir the soul. Sculpturally, we incorporate elements of a human scale and tactile nature—if it can be touched, felt, or related to emotionally, it will have greater meaning. One interest of late has been modestly scaled homes that are highly energy efficient and within financial reach of the first-time homeowner/builder. They can be built by anyone with modest construction experience and are eminently flexible and expandable—homes for the Everyman, with the goal of making compelling design affordable. They respond to the question of how we live today, rather than building a house from the past that we then morph our lifestyles around. The “oneKhouse” is our first venture into offering a series of customizable base designs that meet that criteria and could be built anywhere. Crucial to this effort was the idea that these wouldn’t be stock plans, that there would still be the ability to reflect and respond to the gravity of a site’s inherent characteristics, to sketch and dream about how the house would interact.

Q: HOW DOES THIS METHODOLOGY APPLY TO THE CONSTRUCTION PROCESS?

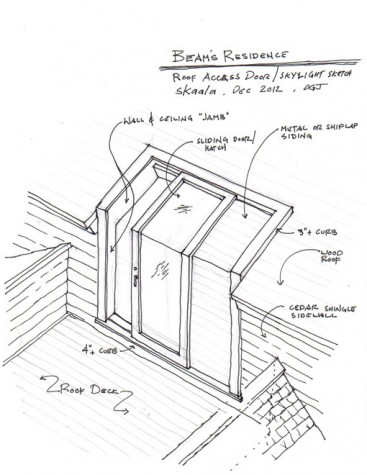

A: Architecture encompasses so many aspects of life. How do we like to dine? How do we cook? What do we want to see from our living rooms? We get into some pretty personal stuff with our clients, like which side of the bed do they sleep on, who gets up first, and who needs more light or less light to stay asleep. You have to get into their lives. A good design requires this deep analytic process and the collaborative efforts of the client, architect, and builder. At the same time, it is not all deep and intellectual. Understanding construction is always important—and, frankly, fun to me. I go back to building occasionally, as with a design-build project four years ago, my own house a couple years ago, and the first of our oneKhouse series that went up last fall. Every time I start sketching something, I am thinking conceptually about how it might go together. Maybe it’s just my personality, but I need to build something—houses, furniture, boxes, whatever—to keep the creative juices going and to retain that physical connection to the process. It has given me a great comfort level when conversing on-site with builders, and indeed, the construction observation part of our practice is one of the things I enjoy most. The same thumbnail-sketch methodology applies itself to construction observation; elements might be altered or added to take advantage of a newly seen opportunity. Often we’ll sketch details over a photograph of a given area, giving the sketch guidance and familiarity. My years overseeing residential construction have proven one thing reliably: design never stops.

American Institute of Architects

Maine AIA: 207-885-8888, aiamaine.org

Skaala: 774-392-0700, skaala.us